PiClock: Waking Up to the Unix Philosophy

I built a clock! It runs Linux. Sounds like quite the over-engineering project, but I learned a ton along the way and was able to flex some muscles that had been lying dormant for a while. I write a decent amount of code, but I hadn’t worked on an electronics project in years and had never really embarked on a 3D modeling or design project outside the classroom.

I discovered the Yayagram a few weeks ago, and my project was inspired by many of the same principles. Although I’m building this clock for myself rather than an older family member, I love the idea that objects can be smart and internet-connected in useful ways without interactive touchscreens. Making smart devices with lower-fidelity input and output can help slow down the feedback loops that we often encounter with the modern internet. I’m hoping my clock can be a step for me away from doomscrolling and towards a more measured relationship with content consumption on the internet.

The Problem

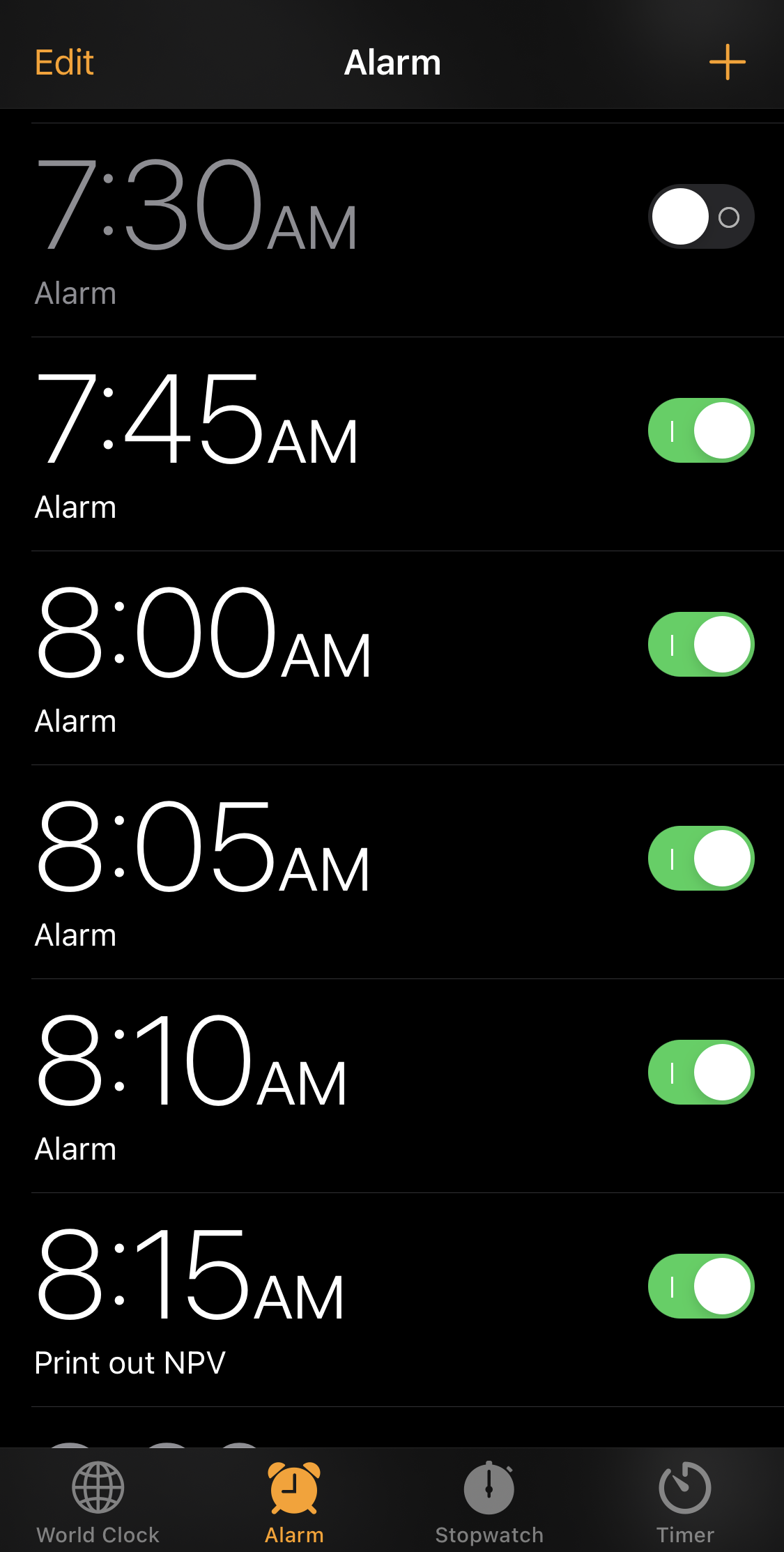

I’m a relatively deep sleeper. I sometimes sleep through alarms, and even when I wake up most of the time, I fall asleep again just as quickly after I hit “off” or “snooze.” I’ve resolved to just setting four or five alarms staggered five minutes apart around the time I want to wake up. It’s not a use-case that’s supported too well by Apple’s Clock app:

On top of all this, needing to grab my phone to snooze my alarm makes it easy for me to keep scrolling rather than get up and start my day. Off-the-shelf digital alarm clocks are a lot less distracting than the general-purpose internet communicators we carry around all day. Still, they generally can’t set more than one or two alarms and are difficult to program when schedules change day-to-day.

The Spec

I wanted a clock that would:

- Let me set multiple alarms per wake-up.

- Not be distracting in the morning when I want to start my routine.

- Provide a bit of news to begin my day without sucking me into an algorithm-powered bottomless doom vortex.

Point #3 means that this clock needed to be internet-connected. But point #2 means that it couldn’t be distracting. This rules out writing a custom app for my phone or something like an Echo Show.

The Hardware

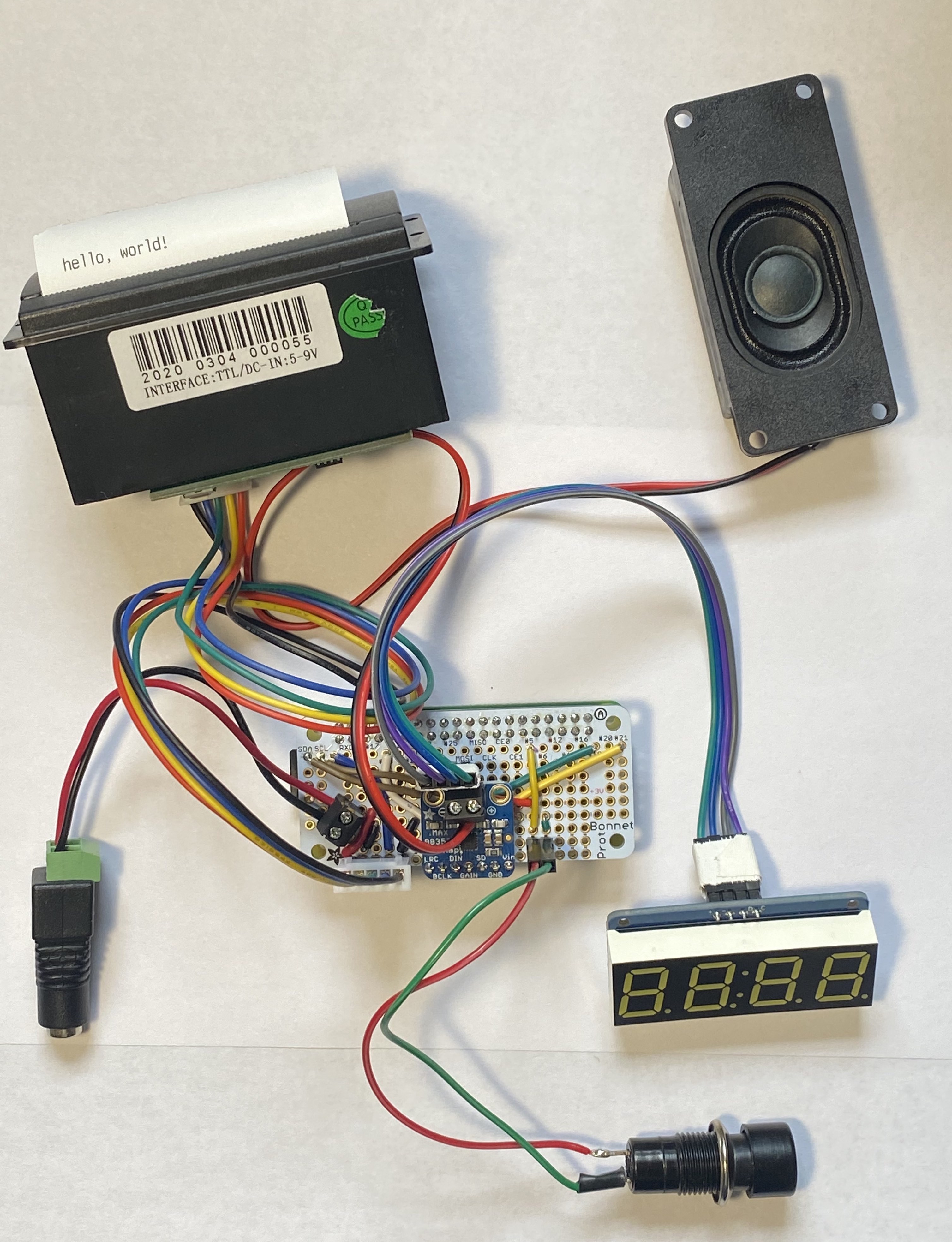

Electronics

My strange alarm staggering requirements meant that I also felt like I’d want to program in custom behavior. With the interaction of all these requirements, I decided to have the brains of the clock be a Raspberry Pi Zero W running a standard Raspbian distribution. For the splash of news in requirement #3, I wanted to have the choice between audio podcasts and small snippets from Twitter and newsletters, along with the weather and recent COVID statistics for my area, so I opted to add in a thermal receipt printer for a more low-screen digital output.

I sourced all the parts from Adafruit, which has a fantastic selection and quick delivery times from their warehouse in NYC to where I’ve been in Philadelphia. I’ve listed a more-or-less complete bill of materials in the Github repository.

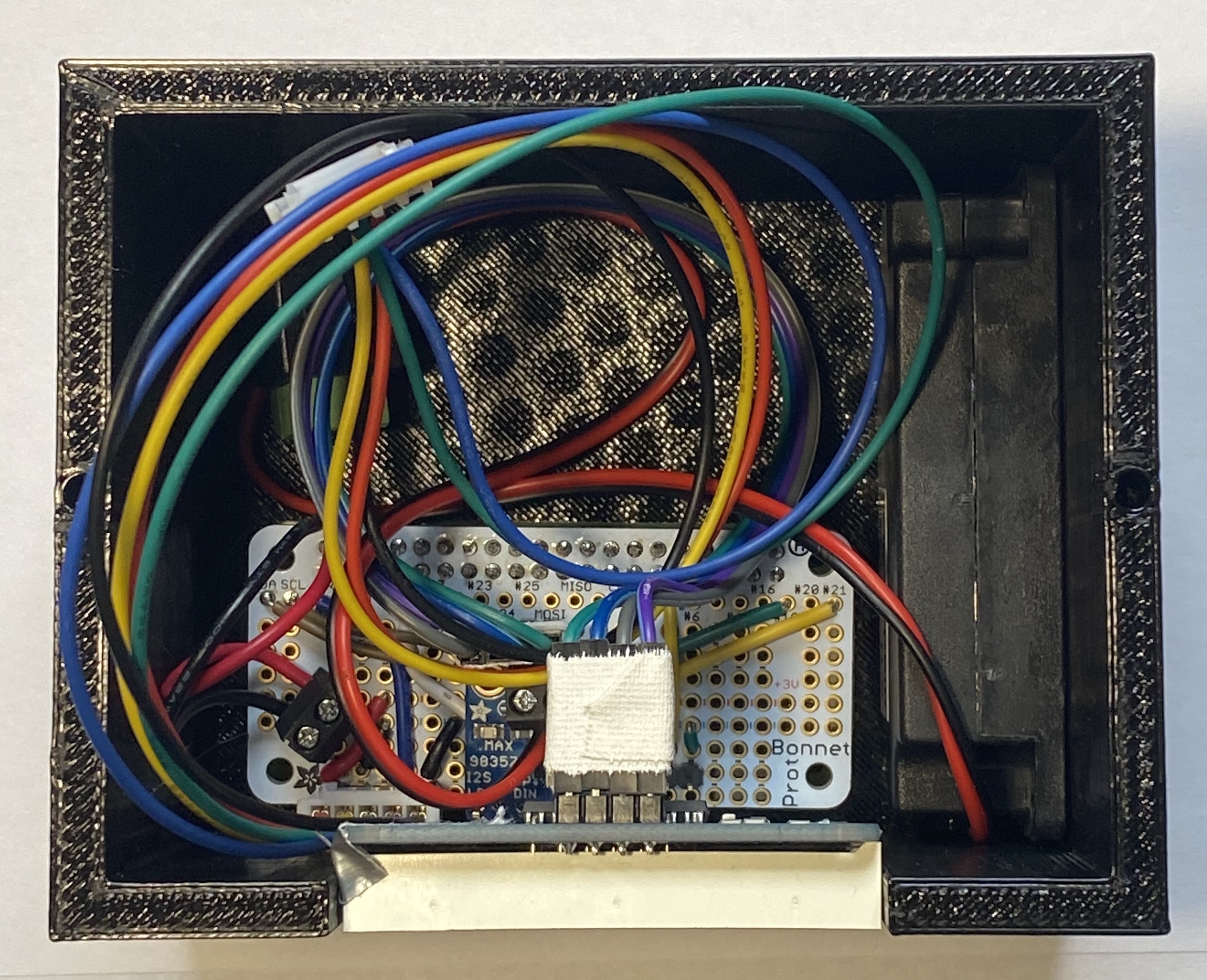

Enclosure

The enclosure was a challenge — my first non-school project in SolidWorks since taking a mechanical design elective two years ago and my first 3D printing project since I was on my high school’s robotics team. If I’d had access to a laser cutter, then that would’ve been my go-to since the enclosure is just a simple box. Engineering facilities at Penn were closed down to most undergrads this year without pressing work to do, so my trusty Printrbot Simple Metal would have to cut it.

I had more issues with bed adhesion and warping than I’d ever encountered before. Once I ironed out the adhesion issues, I couldn’t pull the finished prints off the bed without applying some serious lever force. I ended up investing in a BuildTak FlexPlate to avoid damaging the printer more going forward.

I knew that the software was the most exciting part of this for me and what I was most comfortable with. So I didn’t let myself get started on the coding until after I’d finish the enclosure; otherwise, I’d be left with a mess of wires on my bedside table until the end of time. Ultimately, though, I’m happy with the finished result. It’s about as small as possible while still fitting all the components and looks clean by my bed.

The Software

Adafruit’s whole library stack for their peripherals, I’m pretty sure, is only available for Python on the Pi and Arduino for more basic microcontrollers. This basically made my programming language decision for me, and I’m more than comfortable enough in Python to be happy with that solution.

Before this, my other electronics/embedded computing experience has come

from from Arduino, with its setup(){.verbatim} and loop(){.verbatim}

functions that control the whole project. I was dreading writing all my

code in a single Python while True{.verbatim} loop that would get

initiated on system startup. When I worked on a similar digital watch

project five years ago,

the code ended up being extremely brittle, with different modes and

state riddled all over the place. Fundamentally, I realized I was asking

myself why I would try and write a robust mini-OS for a clock when the

computer it’s running on is already running Linux?

The architecture I landed on is spread among different files and uses

cron{.verbatim} to orchestrate all the behavior. Python scripts

control various aspects of the clock’s functions and are called on

one-minute intervals. Luckily, my display doesn’t have space for

seconds since this is the smallest interval available for cron.

tick.py{.verbatim}: updates the seven-segment displays with the current time.alarm.py{.verbatim}: checks alarm settings and rings an alarm if appropriate.podcast.py{.verbatim}: depending on the command line argument, downloads a new podcast episode from an RSS feed or plays the most recent one.

It’s been my first real foray into building utilities that faithfully

follow the Unix philosophy of doing one small thing well in a composable

way. Settings like alarm schedules are saved in JSON files, and I’m

planning on writing wrapper commands around

jq{.verbatim} to make it easy to

modify settings without dropping into an editor over SSH. It’s

certainly been discussed how composable Unix utilities can lend

themselves well to a productive developer workflow. It was really cool

seeing this approach work well for an embedded system, too, albeit

without actual realtime requirements.

Next Steps

There are certainly some more directions I want to take the clock in. On the software side, I still haven’t played around with the receipt printer much. It’ll be interesting to experiment with data sources and layouts that can work well for morning updates. I also think it could be cool to print out transit directions on-demand. I’m moving to New York City soon, and I always find myself making sure I don’t close out of Google Maps when I’m on the subway, since service can be spotty and I often forget what stop I need to get off on or what train to transfer to next. I’m also thinking about integrating to-dos for the day to track what I plan on getting done in the morning.

On the hardware end, there’s certainly room for expansion. The clock currently has a single pushbutton that I use to interact with alarms. It might be cool to add a time-of-flight sensor for gesture control. Or maybe a fingerprint sensor to allow for different controls based on what finger I press to the sensor.

Code exists in any number of copies. It’s been awesome tinkering and tweaking a physical thing that’s more-or-less one of a kind. And unlike an off-the-shelf product, it’ll be cool to see it evolve over time as I tweak whaat I’ve got add more features to it.